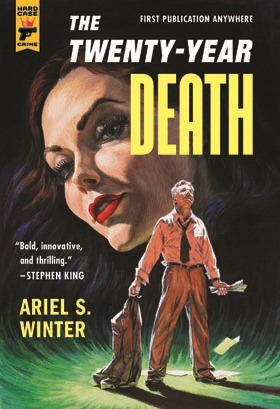

The Twenty-Year Death (Hard Case Crime)

The Twenty-Year Death (Hard Case Crime)

- Hardcover: 700 pages Publisher: Hard Case Crime/Titan Books

- 1 edition (August 7, 2012) Language: English

- ISBN-10: 0857685813 ISBN-13: 978-0857685810

I’ve read trilogies that had five books (Douglas Adams) but I’ve never heard of a debut novel that was, in fact, three complete novels. To be fair, Ariel Winter did – well write isn’t completely correct – publish a picture book. For children. And he has written short stories. For Elle, The Urbanite and McSweeney’s.

Hardly the background you’d expect for a crime novelist, though in his former life as a book seller, he no doubt read some crime fiction. But to decide to write your debut novel, that is in fact three novels, in a genre you have never published anything in previously takes an audacious author. And since he decided to tackle such a task, why not really go out on a limb and write these three novels in the style of three giants of the genre? Or three subgenre of the genre.

That is exactly what Ariel S. Winter did with The Twenty-Year Death. First he tackles Georges Simenon, an author probably more important in Europe than America, but a seminal author of the crime fiction genre. His Commissaire (Jules) Maigret novels and short stories were a kind of bridge between the ‘cozy’ detective stories, where the crime was solved through deductive reasoning, and the police procedural, where the crime was solved through hard work and the collecting of evidence. Maigret appeared in Seventy-five novels and twenty-eight short stories between 1931 and 1972.

The first novel in The Twenty-Year Death is “Malniveau Prison” and, fittingly, Winter has modeled his Chief Inspector Pelleter on Maigret. Maigret, like Sherlock Holmes, was known for his pipes. With Pelleter, it is his ever-present cigars. Both policemen employ a mixed bag approach to detecting, at times relying on pure intuition, at other times on police methodology. A certain laconic manner is also present in both detectives, as is the penchant for mentoring and encouraging underlings. Both also have a fondness for beer and wine, although Maigret is more of the heavier drinker. I think it is no coincidence that “Malniveau Prison” takes place in 1931, the same year that the first Maigret story, Pietr-le-Leton was written.

In “Malniveau Prison” Pelleter is in the village of Verargent, near the prison of the title. He is there to question a serial child killer who has, in the vein of Hannibal Lector, helped Pelleter solve other crimes. While taking Mahossier’s testimony, the killer drops a hint about a series of stabbings that have taken place at the prison but have been hushed up. At the same time, in the village, a body has been discovered lying in the gutter during a rain storm. Initially the victim was thought to have gotten drunk and drowned in the gutter, but it is soon discovered that the man was in fact stabbed to death. Further, he is not known to the people of the village and he also had his clothes changed after having been stabbed.

The victims identity is soon discovered to be that of an inmate at the prison, though he hasn’t been reported missing from there and he is also the father of Clotilde-ma-Fleur, the French wife of the American writer, Shem Rosenkrantz ,who has come to the village to write in peace and quiet. It is only after moving to Verargent that Clotilde discovers that her father, who she has not seen since she was a little girl, is housed at Malniveau. When Clotilde disappears and the bodies of other inmates float out of the ground in a farmers field during the continuing deluge of rain, Pelleter must solve the murder and try and find out who is behind the killings of other inmates.

Winter has managed to capture the style of the prolific Simenon in using many of what were to become standard tools of the trade in crime fiction. Pelleter doggedly follows the clues using a mix of scientific and police procedure (door to door canvasing, questioning of witnesses, the tedious examination of records and files) as well as intuition, logic and the process of elimination getting inside the heads of the characters to ascertain their possible motives– the author, Rosenkrantz – singularly self absorbed, but madly (perhaps too madly) in love with and protective of his new bride-, the killer Mahossier and his psychotic crimes, the local police and business people. He follows many dead ends and pursues red herrings – the disappearance of a group of young boys, the possibility of Rosenkrantz involvement in the disappearance of his wife and how that could tie into the stabbed inmates – and meets many physical and mental challenges, seemingly from both good guys and bad guys until he is finally able to solve a puzzling case.

This first ‘book’ of the trio is totally satisfying and stands on its own two feet. It captures the voice of Simenon perfectly and if left unsigned and stashed in Simenon’s notes could easily have passed as his own work. Indeed, Winter could have stopped here and spent the next decade or two writing Pelleter novels to the utter delight of crime fiction fans everywhere. The plot is masterfully drawn and the sense of place as well as place in time, are wonderful. The characters, both in the French villagers and , the American Rosenkrantz and the melodramatic Clotilde are an achievement. Having succeeded so far, Winter then turns his hand to Raymond Chandler.

To be sure, Raymond Chandler is probably the most important and most copied writer in crime fiction. Many worthy writers have tried to capture that same style – the use of language, his sharp lyrical similes, and some of the finest dialog ever written in any genre. Most have failed. Most end up with parody and pastiche or at best works that are successful but pale in comparison. Chandler (in his own words) took “a cheap, shoddy and utterly lost kind of writing, and made of it something that intellectuals claw each other about?” Winter will have Chandler fans giggling with glee and those same scholars tearing their hair out. His detective, Dennis Foster could be a drinking buddy of Phillip Marlowe’s. It’s not hard to picture them playing chess, chasing the same women. They are both loners, both ex-cops. Both oh so quotable.

Titled “The Falling Star”, book two moves the scene ten years into the future and from France to Los Angles. I’m sorry, it moves the scene to San Angles. Much as Chandler wrote of Los Angles and its environs pseudonymously - Bay City is Santa Monica, Gray Lake is Silver Lake – Winter does the same. Winter even goes so far as to spell ‘okay’ in the "Chandleresque" fashion; “Okey”. But it is not through a few clever name changes and quirky spelling habits that he manages to capture Chandler. His detective, Dennis Foster is cut from the same cloth; He refuses a prospective client’s money because he is ethically unsatisfied with the job and in reality, works for the interest of a character he is investigating.

“The Falling Star” opens with Foster being hired to bodyguard a Hollywood starlet; Chloe Rose – the same Clotilde Rozenkrantz of “Malniveau Prison”. She is still married to Shem, whose career is nearing its ebb, as he works as a script writer, though he has become less important as he sinks in to drunkenness and womanizing, usually with the younger actresses working on his super star wife’s movies. Foster is, as Phillip Marlowe was, not your stereotypical tough guy, but a complex, sometimes sentimental man. He doesn’t like working as a bodyguard, as his self-image is that of a detective. He also doesn’t like the fact that he is hired, in actuality, to NOT do a job and in the end discovers that he was lied to. But, in his diligent way uncovers another crime and as he wades through the Hollywood egos, the single minded police, the shady crime figures and the requisite femme fatale’s he not only sees justice done, but follows his own unique code of ethics which is defined as doing the right thing, not necessarily the legal thing.

I cannot recall a single author who captured Chandler so well. The plot and story could have been pulled from Chandler’s notebooks. The characters could have have stepped out of the pages of The Big Sleep or The Little Sister or any of the novels. And the dialog is wholly satisfying and could have been penned by Chandler from his grave. When Foster narrates, “Hollywood. The talent was crazy and the people behind the scenes were crazier.” It is exactly in that lyrical, cynical fashion that Chandler would have used and when he finishes the story/book with, “That’s why the movies never made any sense. The screen’s not big enough to hold everyone in it.” He adds to the Chandler ideal.

Again, Winter has managed to do, what many have tried, only do it not just successfully but brilliantly. The reader will be left hoping this is not the last time that Winter channels the master.

And for the grand finale, and to wind up this marvelous odyssey of crime fiction, from the cozy/police procedural to the heart of the hardboiled era, Winter takes on another persona from the pantheon of ‘crime fiction gods’ by summoning the "Dimestore Dostoevsky", Jim Thompson. “Police At The Funeral” finds Shem Rosenkrantz in his home town in Maryland. He is now the kept man/pimp of the casual prostitute, Vee, the “should have been enticing, but she is just vulgar,” Vee. Winter pulls out all the stops and would appear to embrace the “three brave lets” that Stephen King spoke of when discussing Thompson; “he let himself see everything, he let himself write it down, then he let himself publish it." It is totally over the top, and sinks to the deepest depths.

Chloe/Clotilde has been institutionalized in a mental hospital for the past ten years, since 1941 when “The Falling Star” took place. Shem has not written anything in years and is mostly forgotten by the public. He is home to hear the reading of the will of his first wife, Quinn where he is reunited with his son, Joe who we met in the opening scenes of “Star”. Shem is hoping to inherit his ex-wife’s estate but when the entire thing is left to his son, Joe, he finds himself nearly penniless and living off the money that Vee gets from her gangster Johns.

Shem has borrowed money from his publishers and from the Hollywood executives and even gamblers and underworld king pins to the extent where they won’t even accept his phone calls or answer his telegrams anymore. Vee is about to abandon him as well, since he won’t be getting his hands on his ex-wife’s money and young Joe holds him in contempt, seeing Shem as nothing but a drunk who abandoned his mother. As the story progresses, Shem sinks deeper and deeper into drunkenness and desperation, but clings to the lie he tells himself that he deserves the money so as to keep Chloe Rose out of a state hospital. But when Joe is killed in a drunken argument with Shem, Shem enlists Vee’s help in staging the scene as an accidental fire.

Winter captures the noir genre and the godfather of the noir movement, Thompson, to perfection. Shem is perfect as a desperate, egotistical, totally self-absorbed, devoid of any redeemable qualities protagonist. Vee is the his perfect accomplice and finds her lineage in the buxom female characters that Thompson and many others of the noir subgenre drew so well. Every single time that Shem has a chance to redeem himself as a human being, he destroys it. His every ‘real’ motive is selfish. At every turn, he is his own worst enemy and has gone from a downward spiral to the final plunge into madness and damnation.

What Winter has accomplished with The Twenty-Year Death will have not just the crime fiction world, but the literary world talking for years to come. To have captured so perfectly the style and voice of three disparate giants and then set them in three separate but interconnected and absorbing stories is truly an accomplishment. It is hard to imagine that he could possibly hope to achieve this kind of tour de force in his future works, but then again, its hard to believe that he could do it in the first place and right out of the gate.

Article first published as Book Review: The Twenty-Year Death by Ariel S. Winter on Blogcritics.

Copyright © 2012 Robert Carraher All Rights Reserved

No comments:

Post a Comment