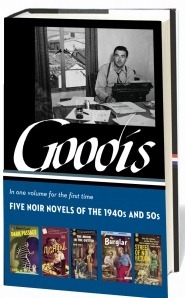

David Goodis: Five Noir Novels of the 1940s and 50s (Library of America)

David Goodis established himself as the successor to Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler with the publication of his first book Retreat from Oblivion in 1939. The year before he had graduated from Temple University, so Retreat boded well for a young author. Unfortunately, his career began at a time that many consider the twilight of the Hardboiled era in fiction. Additionally, the world was on the cusp of yet another Great War.

During the 1940s, having moved to New York City, Goodis scripted for radio adventure serials, including Hop Harrigan, House of Mystery, and Superman. Novels he wrote during the early 1940s were rejected by publishers, but in 1942 he spent some time in Hollywood as one of the screenwriters on Universal’s Destination Unknown. His next novel wouldn’t come until 1946 when Dark Passage was serialized in The Saturday Evening Post, published by Julian Messner and filmed for Warner Bros. with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall heading the cast.

Now, The Library Of America who in ‘97 issued the books, Crime Novels: American Noir gathered, in two volumes, eleven classic works of the 1930s, 40s, and 50s––among them David Goodis’s

moody and intensely lyrical masterpiece Down There. Now, they have teamed with editor Robert Polito to gather five of Goodis’ seminal works of the genre that became known as Noir. Goodis, along with James M. Cain and Jim Thompson, are today considered the ‘godfathers’ of Noir and for good reason. They wrote of ‘the mean streets’ but the people that populated their novels were doomed. They had very few redeeming qualities and the lines were often blurred between right and wrong, good and evil, and hero and villain.

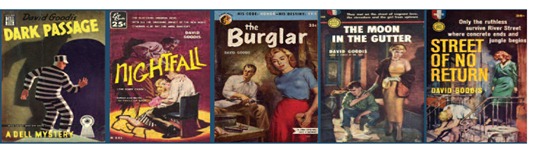

This volume opens with Dark Passage, considered by some as his masterpiece, but regardless, it was his first big break through in 1946, and later on, it made history in a copyright lawsuit. More on that in a minute. The story centers on Vince Parry, who is in prison, convicted of killing his wife. Parry was a decent sort of guy, quiet, never bothered anybody, not too ambitious and worked as a clerk in an investment house bringing home $35 a week. He’d only been married for sixteen months when his wife was found by a neighbor, in her house with her head bashed in. But, before the wife died she supposedly whispered to the neighbor that Parry had hit her with a heavy glass ash tray. The police found the wife's' blood on the ash tray and Parry’s fingerprints on it. To make matters worse, as they are wont to do in noir novels, it came out at trial that Parry hadn’t been getting along with his wife and was seeing other women, the fact that the wife had been seeing other men didn’t make much of a difference to the jury. With no alibi, Parry is sentenced to San Quentin.

He plots an escape, and after carrying out the careful plan, he makes his way out of the prison in a very harrowing and realistic way. But, after the escape, while attempting to hitch a ride, he ends up killing a man. Finally picked up by a woman, Irene Jansen, he hitches back into the Bay area and Irene confesses that she suspected who he was, having followed his case in the papers, and then, hearing on the radio, of his prison break had gone looking for him, guessing his route. Irene agrees to hide him in her apartment and provide him with the means to go looking for the real killer.

The tension, and psychological suspense that Goodis paints during these scenes would become a trade mark. Parry is divided between being grateful for the help Irene provides him and the fear of leaving behind a witness who could provide the police with clues as to his activities. Finally, having difficulties staying hidden at Irene’s apartment because of Madge Rapf, the spiteful and melodramatic woman whose testimony sent him up to prison, keeps stopping by. It seems that Irene has been simultaneously carrying on a friendship with Madge and an affair with Madge’s husband. Irene gives Parry money, and he leaves her apartment, where he starts his quest for the real killers. Along the way he meets a helpful cabbie, who gives him a tip on a plastic surgeon who can inexpensively change his appearance to help him elude the cops.

The novel, with a boost from the Bogart/Bacall movie the very next year, put Goodis on the map as a serious novelist of noir. One interesting aside is that the novel became the set piece in a legal battle between Goodis estate and United Artists Television. The Goodis estate claimed that the UA series The Fugitive constituted copyright infringement. United Artists claimed that the work had fallen into the public domain under the terms of the Copyright Act of 1909 because it had been first published as a serial in The Saturday Evening Post, and that Goodis never obtained a separate copyright on the book. The court found in the estates favor and stated that the law only defined the standing of a work, and should not operate to completely deprive a claimant of his copyright.

In 1947s Nightfall, Goodis would continue to expand his reputation as a master of the genre. Continuing with the man on the run from the law themes of Dark Passage, Nightfall also adds the element of the protagonist on the run from some bad guys. Artist Jim Vanning is on the run in New York City, working as a commercial artist. Three gangster hoods are after him, thinking he has a suitcase full of $300,000 of their money. Vanning doesn’t have the money, but this fact won’t deter the hoods as Vanning did have it, but lost it. From there, the plot get complicated. A detective Fraser is on to Vanning, and though he suspects that Vanning may have stolen the money, he doesn’t picture him as the killer of the man who had the money. Naturally, there’s a dame involved. There always is a femme fatale in these great stories and Vanning has to decide whether the alluring Martha is with the crooks or if she is just a dupe for the crooks and being used for bait. The prose are taut and well crafted as you would expect from an author who achieved cult status. It’s packed with action and scenes that would become standard fare for the authors after Goodis that worked in the noir genre.

The other works chosen here are The Moon in the Gutter (1953), which tells the story of a street hardened man whose sister commits suicide after being raped. With his marriage on the rocks and questions to be answered in his quest for the man that drove his sister to despair, he meets a rich woman. The beautiful Loretta provides him with an escape route out of the mean streets of “Filth-adelphia” , but he learns you can take the tough guy out of the alley, but you can’t take the alley out of the tough guy. The dialogue is perhaps some of Goodis’ most hardboiled. The Burglar (1953) is the story of Nat Harbin, the scion of a family of Burglars who upon finding love looks for a way to leave his ‘family’ and past behind. As Ed Gorman wrote in The Big Book Of Noir, Goodis didn’t write novels, he wrote suicide notes. At heart the novel has themes of crime, honor, loyalty and a futile search for redemption. And finally, 1954s Street of No Return tells the story of Whitey, a singer with a million dollar voice. With that voice, women came under his spell and would sacrifice their body and their soul. He could have been another Sinatra until he met a woman who would prove to be his downfall. The story is told as a tale of Whitey’s past to his wino buddy's in the present and we follow Whitey from that once glorious future through a nightmare descent into oblivion. Whitey now has no future, and only wants the next drink. Along the way Goodis paints the times with hard boiled pictures of Philadelphia and life on the streets and uses historical events such as Puerto Rican race riots as a back drop.

Upon Goodis return from New York in 1950, he lived with his parents in Philadelphia along with his schizophrenic brother Herbert. At night, he prowled the underside of Philadelphia, hanging out in nightclubs and seedy bars, a milieu he depicted in his fiction. He died in January 1967 a week after suffering a beating in a robbery attempt. He died at the age of forty-nine, one month after winning the “Fugitive” lawsuit. But during his life, The Pulp Poet of the Lost and The Prince Of The Losers made a mark on the world of fiction that many noir authors of the present day readily acknowledge.

Library Of America is dedicated to preserving the nation's cultural heritage by publishing America's best and most significant writing in authoritative editions.

Library Of America is dedicated to preserving the nation's cultural heritage by publishing America's best and most significant writing in authoritative editions.

Robert Polito, the editor is a poet, biographer, and critic whose Savage Art: A Biography of Jim Thompson received the National Book Critics Circle Award. He directs the Graduate Writing Program at the New School.

Robert Polito, the editor is a poet, biographer, and critic whose Savage Art: A Biography of Jim Thompson received the National Book Critics Circle Award. He directs the Graduate Writing Program at the New School.

Copyright © 2012 Robert Carraher All Rights Reserved

Article first published as Book Review: Five Noir Novels of the 1940s and the 50s by David Goodis, Robert Polito, Editor on Blogcritics.

No comments:

Post a Comment